Article and Photos by Rich Thom

Clinic Chair Rich Blake welcomed the 25 folks who gathered at our Oak Harbor venue for the Skagit Valley and Whidbey Clinic’s March meeting. General announcements were brief other than to bid adieu to long-time member Al Frasch, whose n-scale Pilchuck Division of the BNSF brought hundreds of model railroaders to Whidbey Island for operating sessions. Your reporter wishes to correct his error in last month’s report, in which he stated that Al hosted 50-plus op sessions. Al’s final session, on March 10th, was in fact the one-hundredth! With anywhere between 11 and 16 crew, readers can do the math: a huge number of model railroaders enjoyed his creation. Modest as always, Al reminded the group that he wasn’t dying, just moving to Arizona. Rich and Program Chair Susan Gonzales reminded all that this was our last meeting at the Oak Harbor venue this season; our April meeting will be a joint one with the Mount Vernon clinic at their meeting place, and the May meeting a field trip at the Lake Whatcom Railway in Wickersham.

Your reporter Rich Thom provided the entertainment this evening, a change of pace from modeling and a look at some 1:1 scale railroading. The title “The Very Last Steam in the World” may seem a brash claim since there are hundreds of tourist steam operations around the globe, and even a few outbacks where revenue, non-tourist steam trains remain in action. So let’s clarify. Featured in the 45-minute video were: (1) the last open-cast coal mine worked by a large, 100-percent steam fleet; (2) the last steel mill entirely steam-worked; (3) the last steam commuter railroad; and (4) the last long-distance steam main line. If you haven’t guessed, all of these “lasts” were in the Peoples Republic of China. Rich made 13 trips there between 1995 and 2007 to capture on film (and tape) this last Big Steam Show.

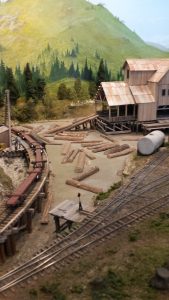

Fig 1. The open cast coal mine at JaLaiNur, Inner Mongolia.

We’ll include just a couple of stills here to give a flavor of the video. Several open-cast (sometimes called open-pit or open-cut) coal mines operated in China using rail systems rather than trucks. Although many used electric locomotives, some used steam traction, even into the 21st century; one even survives to this day in SanDaoLing in China’s far west. The granddaddy of them all, though, was the mine at JaLaiNur, just a few miles from the Russian border in the far north of Inner Mongolia. This enormous pit (Fig 1) was worked by a fleet of no fewer than 54 Class SY 2-8-2 locos, a design optimized for industrial railways and the very last steamers to be built in China (a handful were even built in the early 2000’s). In JaLaiNur’s heyday one could see up to 25 SY’s working in and around the pit at the same time. In the photo, trains of side-dump hoppers at the lower right are being loaded at the coal face, where the seam has been newly exposed, which will then climb out of the pit on a dizzying array of switchbacks to a washing plant at the top of the pit. Other trains are hauling out the spoil, or waste rock, to spoil dumps around the pit’s perimeter.

Fig 2. An SY Class 2-8-2 at AnShan Iron and Steel.

China’s steel mills also had large stables of SY-class (and earlier 2-6-2’s and even American-built tank engines) and the go-to mill for steam enthusiasts was AnShan Iron and Steel’s vast complex in LiaoNing Province. Producing over 17.5 million tons of steel each year (then, a high output), this integrated steel mill—raw materials in, steel out—relied on over 100 steam locomotives to move the incoming materials to its blast furnaces, as well as the outputs of molten metal to the rolling mills and slag to the slag dumps. In Fig 2 is one of the dozens of locos on duty each day, this one the “pride of the shed”, an SY emblazoned with a congratulatory slogan around the smokebox door, and on the cab sides ahead of the number plate, a Red Flag. Both denote something laudable, such as minimal coal use by the loco’s crew. The “Red Flag” award was launched by none other than Mao Zedong himself.

Whereas the SY-class was built for industry—including for example a slope-backed tender for frequent tender-first runs—the final location in the video highlighted China’s largest and most modern main line steamers: the Class QJ 2-10-2’s. The last long-distance run for steam anywhere in the world was on the Ji-Tong line, a 695 mile long, single-track line built to bypass BeiJing’s rail traffic congestion, completed in 1995. A railroad built for steam operation in 1995 was astonishing enough, but it also featured a 28-mile climb which became known to enthusiasts as simply “JingPeng”—a tortuous pass requiring three full horseshoe curves and one high viaduct which spanned no less than a full 90 degrees to surmount. Almost every train required a pair of QJ’s. Rich filmed the Ji-Tong for several years until it finally dieselized in 2005.

Fig 3. An HO model by Bachmann of a QJ Class 2-10-2.

Well-known manufacturer Bachmann also produces a line of Chinese models, but they are hard to find in the US. Rich brought in a pair of these models, an SY and (Fig 3) a QJ. Although the largest in China, the QJ’s would be considered “light” Santa-Fe class locomotives: about 240 tons compared to 350 tons for Santa Fe’s 3800-class for example. Nonetheless, they put on quite a show: the “last” in China, and the last main line steam runs anywhere in the world.

Rich Thom