Article and Photos by Rich Thom

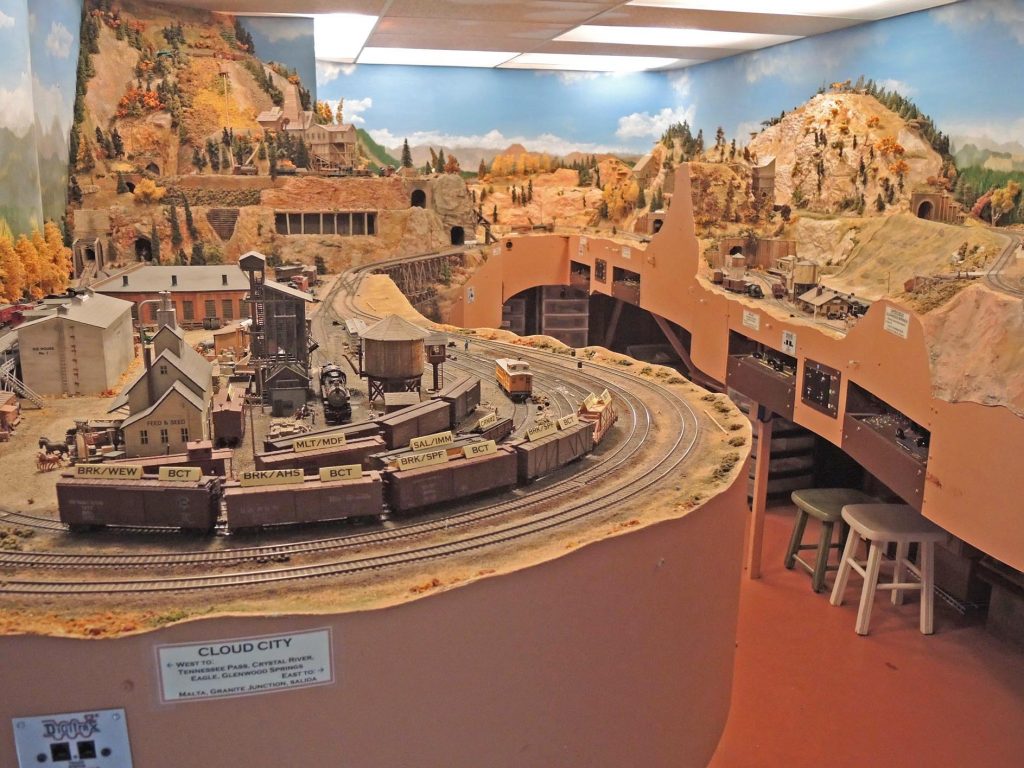

Cliff Aaker, filling in for Clinic Chair Rich Blake on business travel, introduced tonight’s two clinicians who presented two highly interesting talks about track planning for operations. Both presenters are NMRA MMR’s with decades of experience between them. Their layouts are very different not only in the era modeled, but also in their builders’ “druthers” (as layout design guru John Armstrong put it). One shared feature, though, is that both railroads center on Colorado—not surprising considering the fascinating prototypes that this mountainous state offered.Jack Tingstad, MMR was up first with his talk titled “Making an Old Track Plan Work.” Jack’s HO-scale Cloud City and Western RR, begun about 20 years ago, has now been hosting operating sessions for 12 years,

with crew sizes varying between 6 and 8. The main section (Fig 1) is in a ground-floor room 12’ by 21’ in Jack’s home in Coupeville. Jack’s layout was adapted from a John Armstrong plan (thus the “old track plan” descriptor) but whereas Armstrong’s plan featured a “big city” setting, Jack wanted his set in the Colorado mountains in the steam era and revised it accordingly. His “druthers” included:

- “Massive” scenery—extending to the room ceiling and to just feet above the floor in places

- Maximize switching opportunities

- No duck-unders

- “Visually separated” town scenes to the extent possible

- 24” radius minimum mainline radius with easements

- Minimum #6 mainline turnouts

- Micro Engineering track in Codes 83/70/55 for mainlines/passing tracks/spurs

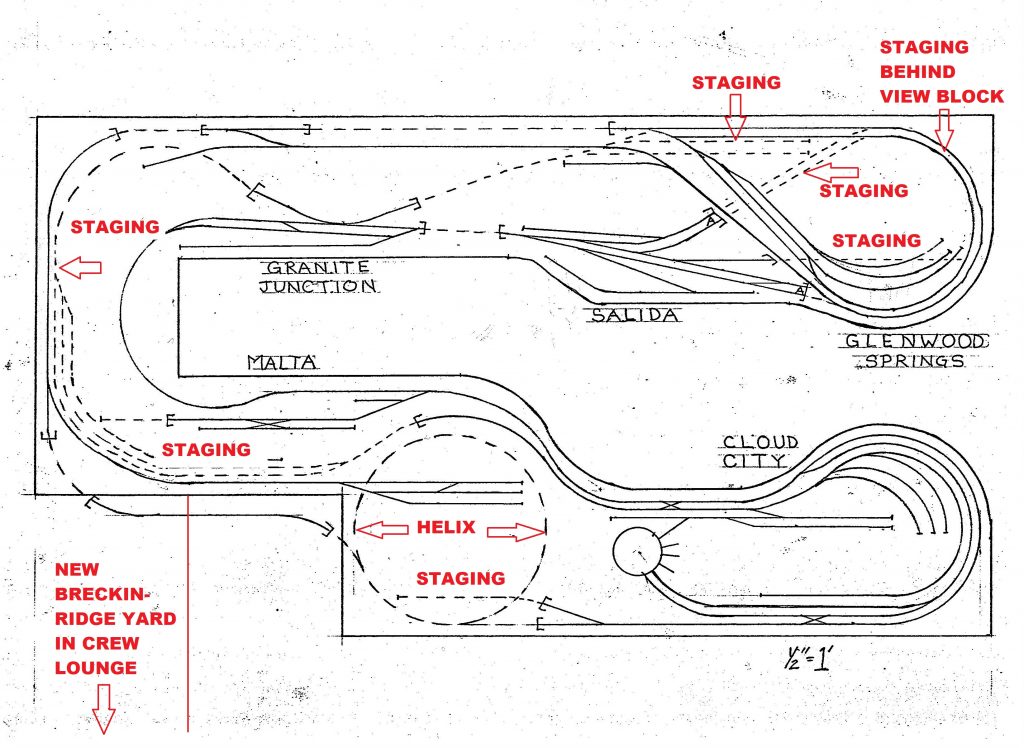

Jack’s resulting track plan is shown in Fig 2.

The plan is “loop to loop” with the eastern and western loops at Glenwood Springs (upper level) and Salida (lower level) shown at the upper right-hand corner of the track plan. The two levels are connected by a 24”-radius, two-turn helix at the lower center of the plan. The layout’s major yard is at Cloud City (Leadville), midway between Glenwood Springs and Salida, lower right in Fig 2. All of the towns are named for actual places in Colorado but their relationships to each other on the layout do not adhere to their actual prototype locations.

Whereas large staging yards, either concealed on lower levels, visible, or in separate rooms, are currently in vogue, Jack built what might be called distributed staging all around the layout, all hidden from view, most below scenery. See Fig 2. He can stage up to 15 trains prior to starting an operating session. A few years ago Jack acquired “trackage rights” to a room adjacent to his original layout space, in which he added a new yard, East and West Breckinridge, with tracks leading through the wall from Granite Junction and Cloud City. This room also functions as crew lounge. The addition greatly expanded operations and adds two crew slots to work the busy yard.

Jack’s “old track plan” certainly works well as this reporter–a regular crew member–can confirm, and he considers it a success. However, there are always lessons learned and Jack shared a few:

- Make sure to provide access to all hidden track; Jack has no fewer than 20 lift-outs, of which 4 or 5 are used frequently, others rarely

- Although they save much space, avoid 3-way turnouts as their complexity can cause loco hesitation and other issues

- Ditto double-slip switches; Jack has one in his town of Malta, as part of a switching puzzle in a small space, but crews can have trouble with it

- Ensure spurs and sidings where cars are to be spotted are dead-flat—otherwise clothes pins or other braking devices are needed to prevent roll-aways

- Use of compound ladders in yards on modest-sized layouts can save space; Jack used them in his Breckinridge addition

Mark Malmkar, MMR, was up next. His layout is about the same age as Jack’s but has traveled many more miles! Begun in Nebraska in 1990, Mark’s layout—built in sections–was moved to two more houses in that state, with revisions to fit the spaces available. Following some years of storage, the layout has been moved yet again to its new home in Oak Harbor where it is now being re-assembled, with plans to considerably expand it as well.

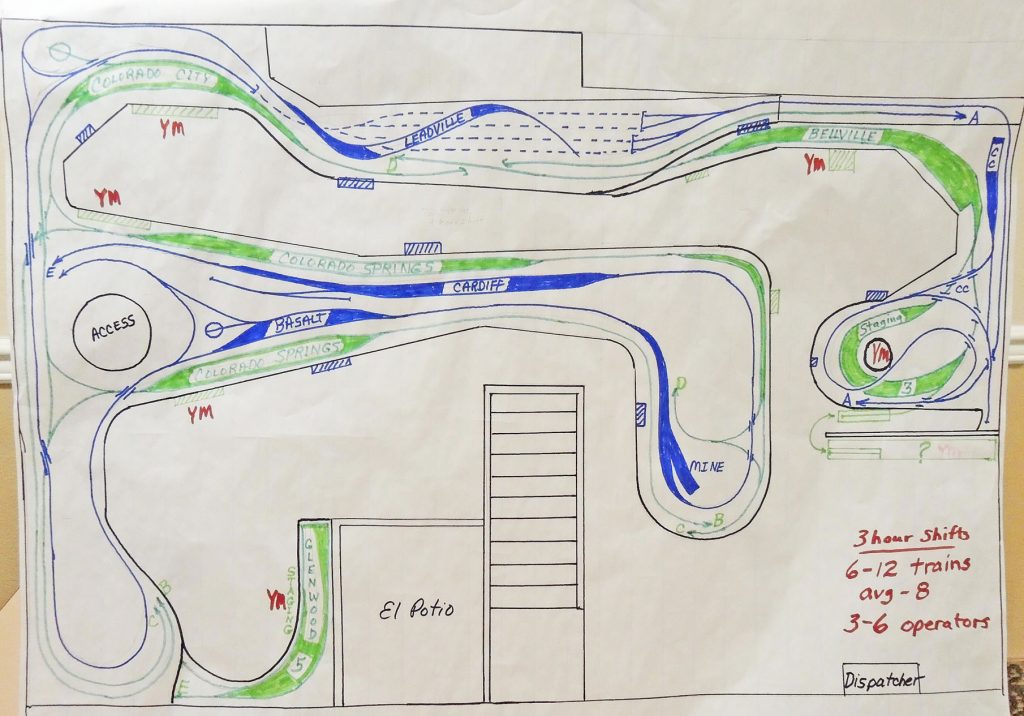

Mark’s current plan for his HO-scale layout in its new location is shown in Fig 3. The space is 40’ in its long dimension. His freelanced railroad is called the Rocky Mountain Central. It’s a two-level pike (lower level is shown in green and upper in blue) with a helix interconnecting the two. Despite being similarly located in Colorado, Mark has far different “druthers” for his layout compared to Jack’s:

- Transition era, 1955, with some steam but mostly diesel

- Town plans replicating prototype as much as possible

- Kansas City and Chicago staging yards originating and terminating trains; most traffic comes from Chicago

- Rock Island, CB&Q, and AT&SF trains cross Rocky Mountain Central’s trackage

- Passenger train emphasis, especially dome cars (Mark’s favorites)

Mark’s layout features 24-inch minimum radius curves and Code 100 track throughout for improved operation. Referring to Fig 3, the sections at the top and at the right of the drawing are mostly re-assembled and in place; the central peninsula and Glenwood Springs at the lower left (now Mark’s office space) are planned for later construction. Mark anticipates 3-hour operating sessions with 6- to 12-trains running, with an average of 8, and 3 to 6 crew on the mainline. Crews could grow to 12 to 14, but aisle congestion, especially where switching districts are close together and on both levels, might make that too optimistic. Mark’s first op sessions will tell!

Great ideas—from modelers with years of experience—for our own layouts.

###

No Comments Yet