Syd Schofield

Editors note: Please welcome Syd Schofield, who will be writing posts in the Grab Iron blog on narrow gauge topics. He welcomes discussions and feedback, which can be made by clicking on the comment link at the bottom of each post.

Model trains, usually smaller than the real life things, generally fit our interests, space, time and budgets. The generally accepted, for various physical, business and political reasons, “standard” gauge (acceptance occurring from the Reconstruction period to well into the 20th century) for most US and Canadian common carriers was four feet 8 and ½ inches between wrought iron and steel rails. Smaller gauges of three feet and two feet also survived among the many other industrial, light transit and amusement purposes as did larger distances for specialized industrial purposes, however common sizes provided for economies of scale in production, operations and exchanges between railroads.

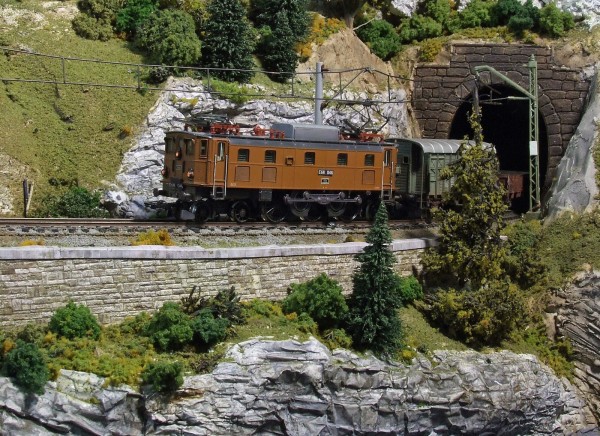

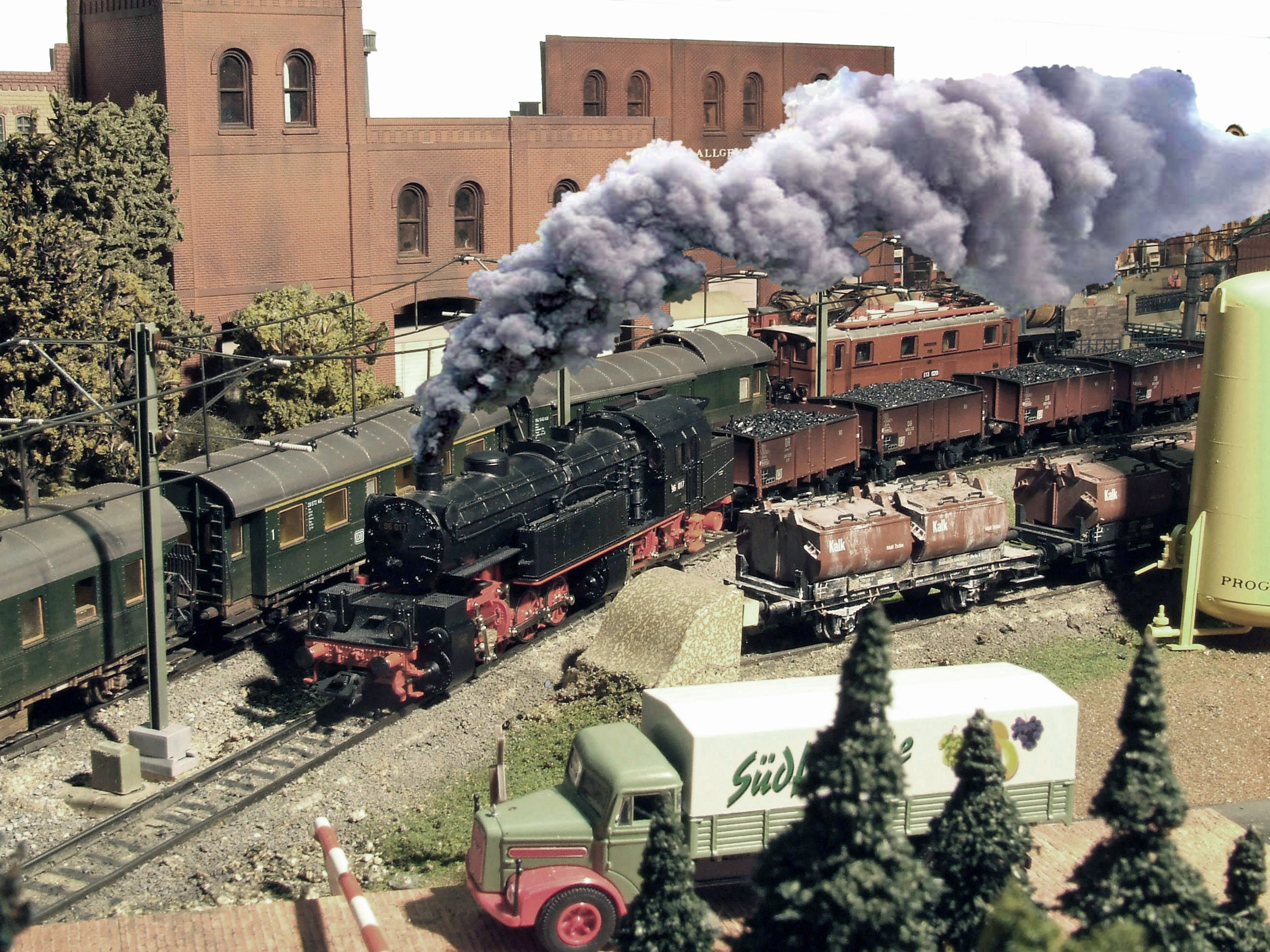

The HOn3 model size designates the “HO” (roughly the half “O” scale) of 1 to 87 parts, the “n” for narrower distance between rails than the standard gauge and the “3” is the actual full size distance in feet (a “30” or similar means 30 inches, versus feet). The general purposes of the full size railroad in this gauge was for smaller, less expensive equipment as well as the lower cost and more agile route preparation. These features made the three foot gauge attractive to any or all of rough terrain, lower capacity, lower capitol investment and short term business situations.

Washington State had at least three three foot gauge common carriers as well as many privately owned and operated by logging and mining interests. There were many three foot railroads and some even had dual gauge operations throughout the Western US, Alaska and other parts of Canada. Some were absorbed by larger standard gauge railroads while others succumbed to the truck, bus and automobile business successes or became historical amusements.

It is this period, simultaneous to the acceptance of the “standard gauge,” that many modelers choose to reproduce from “real” railroads based on historical situation or the merely technically correct for the chosen period creation of what might have been – in HOn3 (or other modeling narrow gauge scales). We would like to explore the activities of modelers in the PNR 4th Division, or anyone else with constructive intent pertinent to the three foot gauge railroads in brief and regular Grab Iron expositions. That is heavy on the “we” as pertains to anyone who would like to offer appropriate comments.