Article and Photos by Rich Thom

Twenty-three gathered at Summer Hill in Oak Harbor for February’s SV&W NMRA Clinic, welcomed by Clinic Chair Rich Blake. After reviewing the calendar, Rich to everyone’s delight showed some photos of Al Frasch’s new N-scale layout that he’s nearly completed in his new home near Tucson, AZ. Al, a former long-time member, newsletter editor, and tireless booster of our clinic as well as model railroad operations in the area, built his new layout in less than two years. Not unexpected from this energetic modeler—good work, Al!

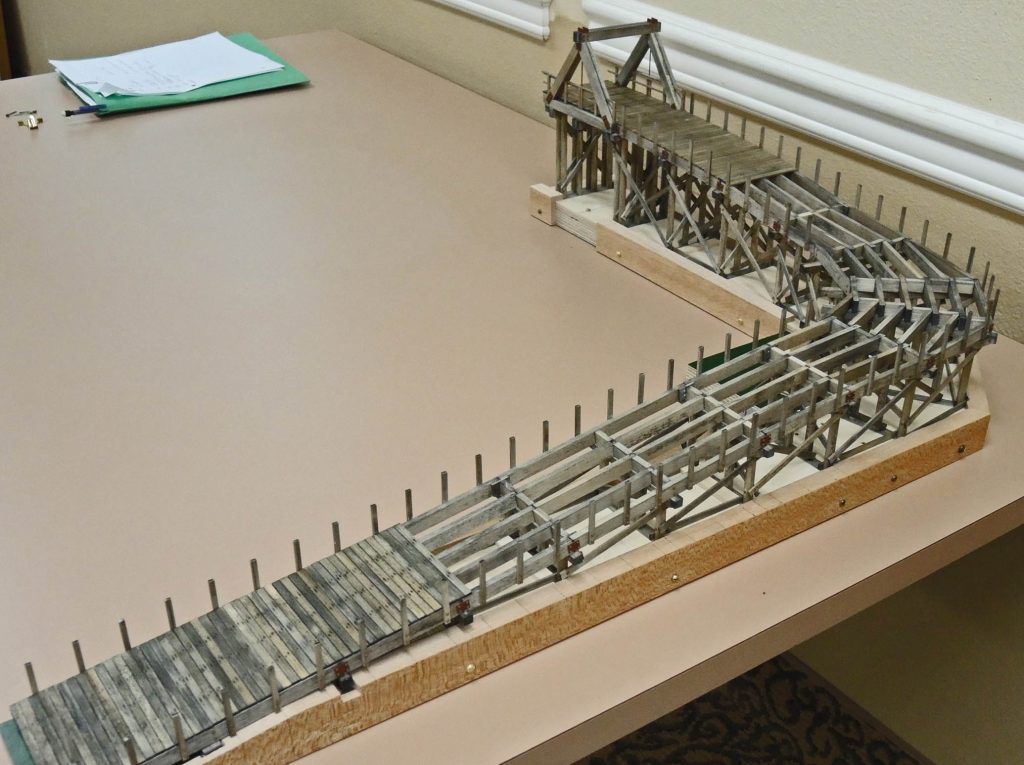

For Show-and-Tell, Alan Murray brought in his O-scale road overpass (Fig 1).

This is a work-in-progress and Alan will describe the overpass construction in detail at our March meeting. He brought it this evening to show the details of the bents and stringers that will (by next month!) be hidden by roadway decking. The overpass has a home: it will feature in one town on Jon Bentz’s in progress On30 layout in Freeland, joining many other scratch structures already in place. Your reporter visited Jon’s layout recently and it will be a welcome addition to our clinic area’s operations-focused layouts. Beta-testing will start this Spring; no pressure, Jon!

The main subject matter at the meeting was “The World’s Last Woodburners” presented by your Grab Iron reporter. That’s a rather sweeping title, because woodburning steam locos were scattered around the world here and there, on preserved railroads, in museums and so forth, but only in a very few places did entire fleets of motive power in everyday, workaday use still burn wood. Your reporter visited two such places in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s. The first was the Philippines.

The Philippine woodburners were found on the island of Negros, one of the country’s 7,000-plus islands. Here were the majority of the Philippines’ Sugar Centrals, 45 of which were founded by American companies, most between 1912 and 1927. Victorias Milling Company (Fig 3) was the largest of them all, at its peak grinding over 16,000 tons of cane each day during the milling season. All of the motive power—in this case 0-8-0’s—burned wood. Combined, the sugar railroads had over 1,000 miles of track fanning out like a spider web from the coast into the cane fields, on several gauges. Victorias had the most unusual: 600mm, which at 1 foot 11 and 5/8 inches was essentially 2 foot gauge—but not quite!

The 3-foot gauge Hawaiian-Philippines system had the most attractive locos on the island, such as its No. 7 (Fig 4), a Baldwin-built 0-6-0. Painted a stunning royal blue, this beauty had slide valves, twin sand domes, and a cabbage stack (with a generator exhaust pipe bent to clear it)—officially the “Rushton Improved Stack.” The center drivers were flangeless—on an 0-6-0!—which tells you something about track curvature. The ungainly crib built onto the tender signals that this loco burned either wood or bagasse, in this case the latter—cane waste from the crushing process. It must be kept dry, hence the roof, and free from the stack’s embers, thus the ember shield of oiled canvas between cab roof and the roof of the bagasse tender.

A Shay on a sugar cane railroad? Yes, and here it is (Fig 5) on the Lopez Sugar 3-foot gauge system. One may wonder why these hill-climbers found any use on mostly-flat terrain. The answer was that they were hand-me-downs. Turns out the northern hills on Negros Island were forested, in especially-valuable woods such as mahogany, and a company named the Insular Lumber Company (ILCO) was formed to harvest it all. They imported numerous pre-owned Shays and even an 0-6-6-0 Mallet to haul logs to the mills, most from a standard-gauge lumber operation in the U.S. Lopez No. 10 (Fig 5)—a common 60-ton, 3-truck type built in 1924—was re-gauged from standard to, first, ILCO’s 3’6”, then to Lopez’ 3-foot. Have many locos been so frequently re-gauged?

The second country where wood-burning power dominated was Paraguay, one of South America’s two land-locked countries. It’s a long story kept short here, but the Ferrocarril Presidente Carlos Antonio Lopez ran 232 miles from the country’s capital, Asuncion, to Encarnacion on the Rio Parana, the border with Argentina. The first train ran in October 1861, and for the rest of its days was entirely operated with wood-burning steam locos. The backbone of its “modern-day” roster was a fleet of 14 2-6-0’s acquired from North British (Glasgow) in 1910: No. 101 in Fig 6 is one of them, seen at Encarnacion. Specifically designed for burning wood, note the steam dome but no sand domes; slide valves; European-style buffers on hinges; and straight stack—ember-sparked fires weren’t a concern, apparently. The auxiliary wood car behind the tender was standard on all trains. But where’s the air pump? There wasn’t one on the fireman’s side, either: Paraguay’s trains had no train brakes whatsoever, relying on a steam brake on the loco.

Most of the wood in the region was a very hard variety called quebracho, literally “that which breaks”, and here (Fig 7), balancing on the woodpile (you try it!), your reporter captured the third crewman—the assistant Fireman—handing off the odd-sized “sticks” to the Fireman to feed the firebox. The Firehole on these locos was larger than on coal- or oil-fired locos to deal with the large, odd-sized wood.

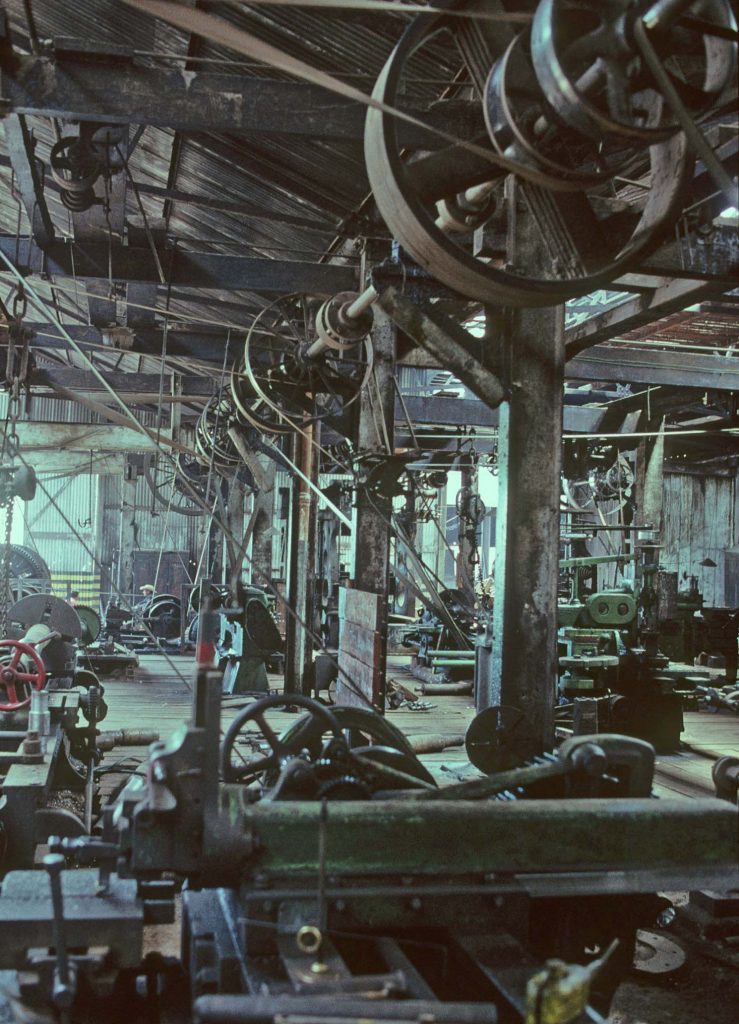

A highlight of Paraguay’s railway was the shop at Sapucai, located about midway on the system. It performed all the usual functions of such a shop, handling full rebuilds of locos from the frame up. All the usual machinery was there—wheel lathes, mills, drill presses and the lot–but Sapucai’s was powered by a steam engine and a delightfully-complex overhead shaft and belt system (Fig 8). One had to watch one’s back when wandering through this place! What a facility to model! Many of the tools had several different sized pulleys above them to enable, by shifting the belt, different tool speeds.

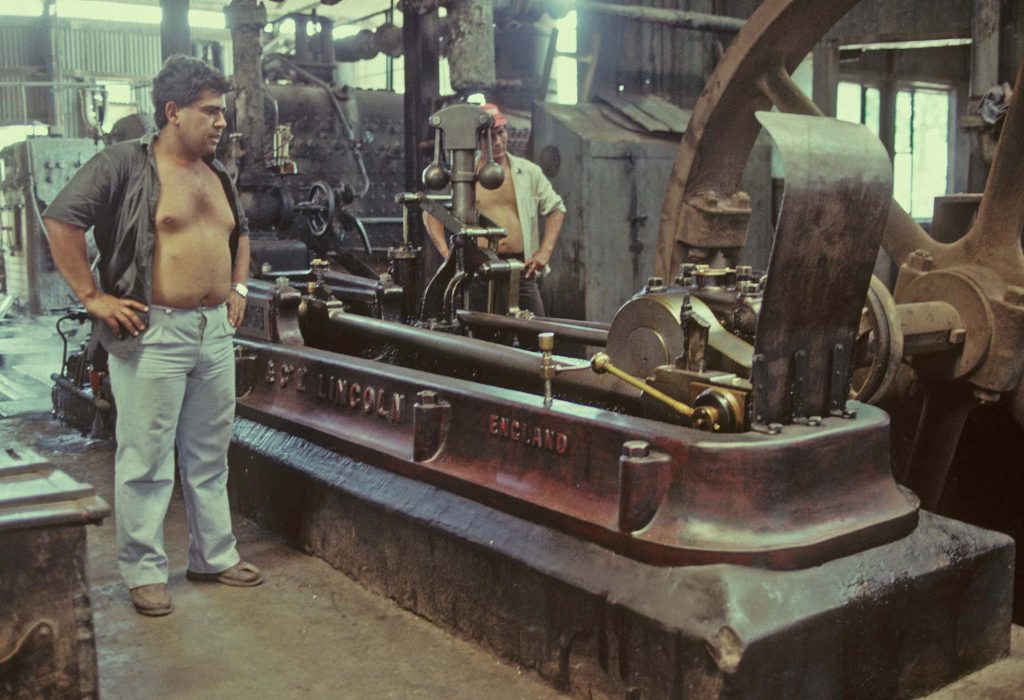

The shop was powered by a Victorian steam engine (Fig 9) built in Lincoln, England; there was no plate to determine the build date. And since the theme of the evening was wood-burning steam, will it surprise the reader to learn that the shop’s boilers were—what else in this country—wood-fired? Finally, we all know what “plumber’s butt” is. Which begs the question: what phrase best describes our two shop workers above?

###

Love your reports. Next best thing to being there. Jim here (trapped in Tacoma)